A case for forgetting

We’re tracking and recording so much of our lives — without actually seeing the life within

First of all, whatever your age or orientation, go see Pixar’s new movie, Inside Out. If you need more reason than “it’s Pixar,” try this: it’s a sophisticated, hilarious, brilliant, warm, beautiful, and perfectly paced film that — finally — stars a girl who is not a princess.

While nominally about the emotions in a young girl’s head, the movie is also fundamentally about memories — how they stay with us, how they influence us, and how our feelings about them change.

One of my favorite scenes was one in which we learn that memories — which take the form of small, colored globes — sometimes have to be cleared out for others to survive. I won’t say more about it, so as not to spoil a truly beautiful sequence, but it helped me remind me of a fundamental truth about our lives: not every memory has equal value.

This might seem self-evident, but you wouldn’t know it by looking at all the ways we track our lives. All of our apps and social networks aren’t really built to support a life of change and variance. And if that’s the case, maybe it’s worth considering how these digital tools might be taking something away from us — and how the very act of remembering, left in our own hands, might bring unexpected rewards.

1: Recording

One of the differences between previous generations and our modern world is that, increasingly, our lives are tracked and recorded. Emails, photos, texts, calendars — they never really go away. More than their perpetuity, though, is their pervasiveness: we record everything. What you ate last night, whom you saw, where you went. Between the accounts you have on (for instance) OpenTable, Uber, Instagram, Fandango, and Yelp, you could replicate a huge portion of your life to an astonishing degree of accuracy. And that’s not even relying on your credit card statements or the history on your Google Maps searches, both of which contain an unprecedented level of detail about your life.

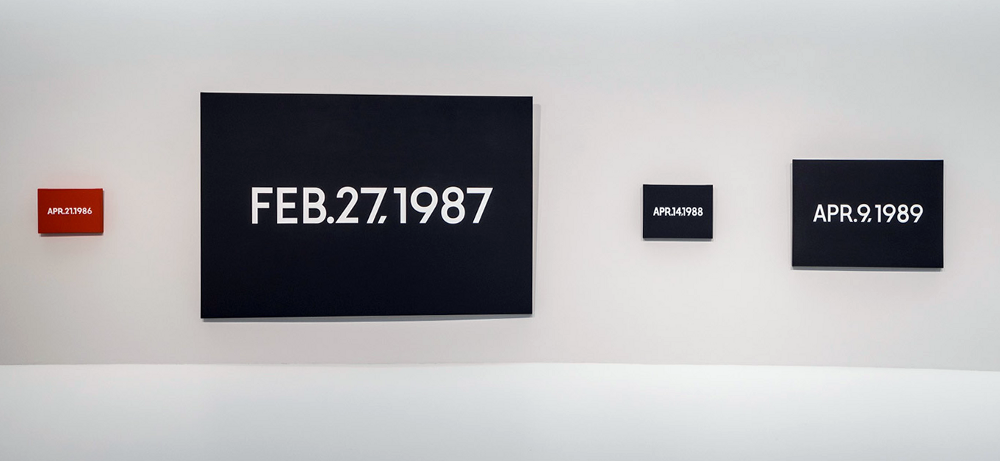

Well, not really unprecedented, at least not completely. One of the 20th century’s great conceptual artists, On Kawara, made a career out of measuring and recording his life. The Guggenheim curated a blockbuster retrospective of his work earlier this spring, and seeing all of these pieces together for the first time added an immense power to them.

His date paintings, for instance, in which he painted the date of whatever day he worked on the canvas: when you see one of these paintings, it’s intriguing, but when you see hundreds of them all together, the sheer regularity of it astounds. Each painting is no more or less than a marker of the day that he painted it: their very existence records his primary tasks on those given days. And he did this for more than 3,000 days over 30+ years.

Similarly impressive is his piece entitled I Got Up, which encompasses about 1,500 postcards that he mailed to friends, once per day over several years, with nothing on the card other than the words “I got up” and the time that he arose that day. He also has maps recording his walking paths day after day, lists of people he met day after day…

Until the last few years, there is probably no human in history whose life has been so meticulously recorded. Which is amazing, but still I had one glaring problem with it all: after two hours absorbing thousands of details about On Kawara’s life, I still had no idea who he was.

I tend to think that scale absolves art — meaning that we don’t usually judge incredibly large or incredibly small works solely on their merits; their size requires a different (and usually more forgiving) rubric. In the case of On Kawara’s work, the scale is the art. There’s nothing there except the vast scope of his efforts. In these pages and postcards, we see the structure of his life, but it’s strangely vacant. We can piece together the movement, but can’t see the thing that moves.

On Kawara’s work required enormous effort on his part (and on the part of his wife, it should be mentioned, who assisted him throughout life, albeit mostly in shadow). Recording things about our lives, though, is so easy. We do so much of it under the guise of “sharing” — our most unexamined and most celebrated modern virtue—and the remainder is done automatically, or at least by inference: even if we don’t write “went to work” on a sheet of paper, we can tell quite easily that we were there by looking in our email archives.

More impactful, I think, is how present our recordings are. So much of our past is kept in front of our eyes by apps and sites that use the paradigm of a stream or timeline. They are built to facilitate a backwards glance as easily as a forward step.

I’m not saying that this is inherently bad, of course. This sense of longitudinal consistency can boost fitness or help us kick a bad habit, and all of us have, at some point, found the warmth that comes from stumbling on a years-old post and remembering a good moment. (The popularity of apps like TimeHop seem evidence enough of our love for this “accidental” discovery.)

Just like On Kawara’s life work, though, I think these data outline our lives without describing us. These discrete memories, however well recorded, don’t tell us anything about ourselves.

Maybe that’s because they aren’t actually memories — they’re reminders.

2. Remembering

People who study these things (i.e. scientists) have understood for decades that memories are not fixed. The human brain is notoriously poor at objective recollection, influenced not just in how we perceive something at the time it’s “recorded,” but how we perceive the memory when we try to recall it.

This malleability might scare some, but it’s actually vital to our own development. We constantly and naturally (and often subconsciously) adapt memories to help build and define our own sense of self. We tell certain stories about our past, we highlight certain details of an event, all to help craft the narrative we wish to tell about ourselves.

This is how we’re able, for instance, to take an embarrassing or sad memory and make it instructive instead of depressing. (Any article or graduation speech about the blessings of failure is doing exactly this: taking a “bad” memory and imbuing it with inspirational meaning.)

We don’t just adapt, of course — we elevate certain memories above others, granting them importance in our lives out of proportion to their objective reality. A first kiss might be seconds long, but it might be the turning point of your life. A flubbed presentation might have been one of hundreds you’ve given, but you might remember it more than any other. Some of this is done subconsciously, but in the past few decades, psychologists have begun to recognize the power we have to control this narrative.

The psychologist and author Marybaird Carlsen, building on ideas developed by Harvard’s Bob Kegan, summed this up poetically:

“No one can hand us a ready-made meaning; nor is something meaningful until it has been born within ourselves and woven into the tapestries of ourselves.”

Funny thing about emails and tweets and Facebook posts, though: they resist meaning. Twitter has no idea if one tweet is more meaningful to you than another, and no way to display it differently if it is. These posts also don’t change — they’re fixed in a database somewhere (data integrity notwithstanding) — and as a result, they don’t allow us to change. Seeing these digital reminders in front of us constantly prevents us from triaging memories, the natural sorting and discarding and adapting and appropriating that we need to evolve.

It’s not just our own sense of self that needs to change, of course. What about others’ perceptions of us?

Every business publication has printed a story of a job applicant who was passed over because the employer found an embarrassing photo online. I’ve heard repeated stories from friends of mine who have decided to stop dating someone based on something found in a Google search. And which of us hasn’t said “thank god there isn’t evidence of the stuff I did in middle school/high school/college”?

We change, whether it’s the result of conscious effort or the natural process of learning and maturing. But the digital artifacts of our history are omnipresent, unchanging, and unforgiving. Not only do we ossify in our own eyes, we remain frozen in others’ eyes.

It’s like always having your parents around, and they’re always bringing out that one photo of you naked in the bathtub. We can’t move on, we can’t grow up.

I’d like to believe that seeing our beginnings would only inspire others to celebrate how far we’ve come — the delta of our lives, not the darkness.

Right now, though, that just seems naively optimistic.

3. Living

It’s worth clarifying that I’m not encouraging you to delete your Facebook account or erase every email in your archive. I’m not suggesting that the only way to move forward in this life is by scrubbing the Internet of every mention about you (as if that were even possible).

I do wonder, though, if we might benefit from some distance. Distance from our earlier lives, distance from yesterday and last year and the previous decade. I wonder what would happen if we relied more on ourselves to make the connections between our memories, instead of letting a well ordered list do the heavy lifting.

Everything happens in context. (Even flying is only impressive in the context of gravity.) Sometimes, though, that context has a broader horizon than we realize: an event that seems innocuous after one year might take on tremendous meaning after five. Context requires distance that we don’t seem to get with the constant accessibility of an unchanging past.

I’m also hoping that we find a way to grant others some flexibility. We can disagree, we can dislike another’s actions, and we should call people out on destructive behavior. But as the records of our lives become more detailed and more accessible, I hope we can see them as an outline and not the full picture.

In a sense, I’m making a case to forget what is worth forgetting, to take back the power of telling our own stories — and, just as importantly, to let others be the author of theirs.